Shapeshifting Performance explores performance practices stemming from Indigenous theories of incessant metamorphosis. Mesoamerican theories of transformation powerfully expand Western theories of acting, of becoming other, doubling, beyond the conventional frameworks of representation and imitation. In Mesoamerican metaphysics, energy links and transforms all that exists; everything is alive and interconnected. People, things, and the elements can change shape, become other, because they share an essence—“teotl” or energy. Humans are not considered ‘unitary’ or ‘singular’ beings but, rather, share the same essence or energy that powers all else. Several Indigenous languages do not distinguish between humans and animals—in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, they both fall into the category of “los vivos” (the living), as Roberto Martínez González notes. The connection among all that share this co-essence is such that contemporary Mesoamericans consider environmental degradation a form of genocide, not ecocide.

This shapeshifting is a form of nahualismo, stemming from nahual, which is, most simply, one’s spirit companion, one’s guardian. Theories of transformation differ throughout the Americas. For the Nahuas (or Aztecs), the nahual entailed doubling. Every person, in Nahua philosophical system, is born with at least one nahual, usually an animal spirit, but not everyone knows they have one or what shape that nahual takes. The basic feature of nahualismo is “a type of shared animality.” Every human, in this worldview, Martínez explains, has at least two bodies, one that inhabits the quotidian world, and one, “usually an animal… that lives in the forest, in the heavens, [the underworld], or in some mythological place.” They are joined by an ‘entidad anímica,’ an animating entity or vital force. Some Indigenous communities spread ash around the newborn’s cradle in hopes of identifying their nahual by the animal’s footprints. The person, though connected, is not one with their nahual. [In the Amazonian Shamanic practice, on the other hand, the shaman incorporates or ‘becomes’ its nahual—so the combined entity is one, not two.]

Nahuales can take animal forms, but they are not ‘real’ animals. They have some tell-tale features if one knows how to recognize them—they’re larger or smaller than animals of their species. They have extra digits or there’s something odd about their eyes. But they are not representations of an animal, nor simulacra. This essence “animalizes itself to act in the human world.” Usually thought of as an animal, say a coyote or a snake or a hummingbird, the most powerful nahuales are meteorological– a lightning bolt, wind, or fire. Yet, nature too needs nahuales to protect its rivers, forests, mountains and so on. Nahuales can be individual or collective—a person or a people can have a benevolent nahual that attacks others brutally to defend them. Nahuales can, however, be evil and turn against their own people. They can, and do, according to Alfredo López Austin, enter and ‘nahualizar’ (transform) “humans, the gods, and animals” altering them, for good or ill. If humans take an animal shape, they do not ‘become’ an animal—they remain aware on some level that they’re human. But they are not pretending to be an animal. If one’s nahual is killed or seriously injured, the human can suddenly fall ill or even die. The essence, or co-essence, linking human to the nahual however never dies. It goes to a special place where it is scrubbed clean of all personal characteristics, memories, and histories and transferred to another being born of the same species or kind. Energy in motion, the nahual transforms but never dies.

Most people, past and present, are not aware of this co-essence, of having this other body, of sharing a vital force with another being. Yet in Mexico today, especially in Indigenous communities, people of various social classes and ethnic backgrounds tell of animals, even plants, that respond to their or other’s illnesses. Within this general acceptance of nagualismo, Martínez notes, there are special humans, ‘human-nahualli’ (hombre-nahualli he calls them), who have a stronger, more powerful essence who “can use their counterpart … at will.” They can control and willingly inhabit their nahual’s shape to cure or hurt others. The human-nahualli is a special being at birth. However, to possess the necessary qualities to be a ritual specialist or wield their considerable power they need to hone their skills.

The nahual’s capacity to transform itself seemingly “magically into an animal or natural phenomenon,” can augment the nahualli’s social and political power. Nahualismo, Federico Navarrete Linares notes, is a highly ambiguous force. Not just a “magical practice” and a “cosmovision,” it also includes the “deception and dissimulation” usually associated with acting and political posturing. Human-nahualli’s, those of ‘superior’ strength and talent, might well use their powers to impress their followers and stun their enemies. He tells of a certain “cacique, in order to make his soldiers happy, became an eagle and went into the sea, showing that he was also conquering the sea…” A list of similar exploits by powerful figures would include historical and contemporary examples, although they would be understood not as nahuales but in language and framework of their own socio-cultural contexts.

The nahual, for Mesoamericans, extends beyond human energy, connecting and communicating “between the different strata of the universe.” The human-nahualli links societies to nature and to the cosmos. The energy linking humans to the natural world and to the cosmos takes various shapes, all ‘real,’ all involving forms of doubling or embodying, all inter-connected defying all subject-object, self-other, human-animal, nature-culture, animate-inanimate distinctions produced by Western thought.

***

This study focuses on nahualismo or shapeshifting through the prolific performance work of Jesusa Rodríguez (b. Mexico, 1955) or simply Jesusa as she is known in Mexico. From her 1999 essay ‘Nahualismo: An Aztec Acting Method,’ Jesusa examines, adapts, and applies performance practices and strategies based on this ancient, living, praxis. Her work demonstrates that shapeshifting is more than an artistic doing. It involves a complex, multidimensional way of knowing, being, embodying presence, surviving, and acting in the world. Jesusa draws from nagualismo, I will elaborate later, as a way of thinking not as but through another.

Shapeshifting, as in the example of nahualismo, is a highly complex concept with divergent characteristics across time and geographies, but in some form or other it remains a living, powerful, and resilient force throughout Indigenous communities in the Americas.

Some contemporary artists recognize this ‘essence’ or energy as shapeshifting. Native Canadian artist Tomson Highway (Cree) considers the Trickster (“a spirit half-human and half god” 25) the collective and essential force of cultural survival. For Mesoamericans, nahuales connected to a collective were known as nanahualtin, “associated with human groups.” Highway’s trickster, like the nahual, looks after his people. He argues that “The Native Trickster… is a shape shifter. S/he can change into and be anyone or anything” (121). “In Cree and other Algonquian languages, the world is Mantoo, meaning Spirit, not a ghost but an energy’—represented as neither a man nor a woman but a thunderbolt.” “’Even when confronting the ‘horrors of European history,’ the ‘Indigenous collective racial memory of this catalogue of misery, this collective crime of the dreaded human race,’ this energy persists…” As such, he continues, the trickster figure contributed to Native survival, “sav[ing] an entire race of people” (97).

Gloria Anzaldúa writes “nagualismo (its alternative spelling) is an alternative epistemology,” (32), part of “the oldest known religious practice, one in which the shaman or nahual undertakes a ‘journey’ (or trance journey) to the underworld, upper world, or other worlds… For Anzaldúa who educated and immersed herself in the Mesoamerican metaphysical traditions, shapeshifting maintains the same essence although the appearance may change. “the creative process is an agency of transformation” (35).

What does a ‘nahualist’ resistant performance practice look like?

How does one transform into someone or something else?

Jesusa draws on nahualismo to respond to a question that theatre practitioners have long asked themselves: “Where and how,” she asks “does the act of transformation occur, the transformation into another person? ‘As if’ one has been possessed… In what moment does the magic occur that transforms one person into another, different from themselves?”

Transformation, not change, is key to Mesoamerican thought. Nahuales do not in fact change into other beings. They share their essence, their energy. James Maffie in Aztec Philosophy, states “there exists just one thing: continually dynamic, vivifying, self-generating and self-regenerating sacred power, force, or energy… teotl” (21-22). While change entails two different ontological categories, transformation maintains ontological sameness (Maffie’s ‘just one thing”) although it can have many guises. A caterpillar and a butterfly are different outward manifestations of one being—they have the same DNA. The dual figures of creation are in fact one, Ometeotl (literally, “Two God”), the god of duality, that encompass seeming opposites: “being and not-being, order and disorder, life and death, light and darkness, masculine and feminine, dry and wet, hot and cold, and active and passive. Life and death, for example, are mutually arising, interdependent, and complementary aspects of one and the same process.” Things may seem diverse, ‘as if’ they were something else, but everything is connected, part of an ever-transforming force.

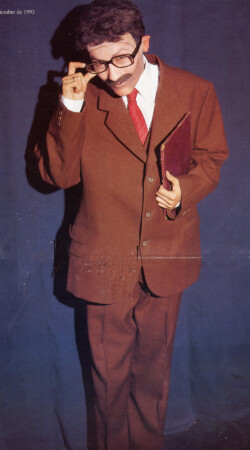

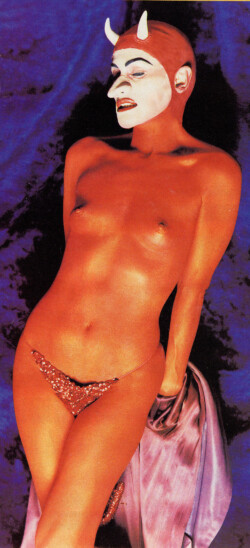

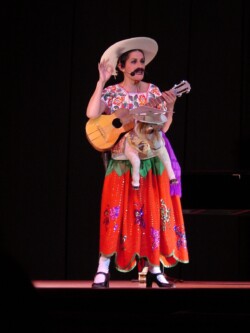

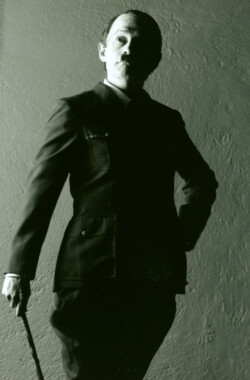

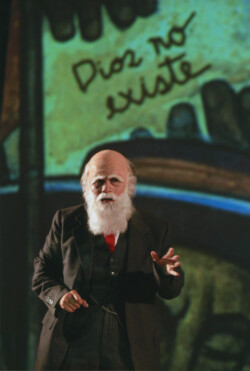

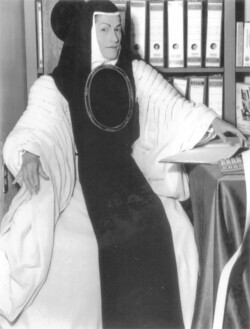

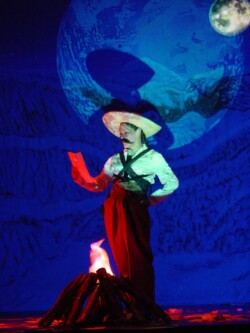

Jesusa, a queer, mestiza artist, transforms constantly, and seemingly effortlessly, into a staggering array of figures. As a child, her sisters called Jesusa “a nahual… She can transform into anything she likes… She has a very special magic… she has no limits.” While she would not call or imagine herself a nahual, she thinks through nahualismo to embody personages onstage. She has been the famous 17th century nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Charles Darwin, Donna Giovanni, Hitler, Columbus], and many other famous and infamous luminaries. She embodies non-human figures including God, Coatlicue (the Aztec’s mother of the Gods), animals and corn. Jesusa has presented over three hundred impersonations and political critiques that she devises and directs. She also transforms social space. The cabaret spaces that she and her wife/artistic partner of forty years, Liliana Felipe, opened from 1980 through the 2000s changed performance practice in Mexico. As an actor, director, performance artist, activist, and politician she knows that life, like art, is an unending process of creative energy, that “every single day one starts anew.”

This brilliant, provocative, and astonishingly prolific theatre actor/writer/director/set designer, cabaret artist, lyricist, activist, and politician (national senator and currently advisor on Indigenous Affairs to the President of Mexico) may not be a nahualli but she is powerful. “When Jesusa Rodríguez is on onstage, on camera, in the streets protesting the latest outrage — she may be the most powerful woman in Mexico… ” Pulitzer Prize winner Tim Weiner wrote in the NYT back in 2001. Elena Poniatowska, Mexico’s “grande dame of letters,” also considers Jesusa Mexico’s most creative female force after Frida Kahlo. She is “essential,” Poniatowska continues, both to Mexico’s political and cultural life.

Jesusa became immersed in the Mesoamerican world, which remains alive and palpable in contemporary Mexico, when she stumbled on Cuicuilco, one of the most ancient archaeological sites in the Americas located on the outskirts of Mexico City. She was seven years old and got lost on her bike. As a child, she decided to become an archaeologist. She has always read deeply and studied with Mexico’s most eminent scholars and worked closely with Indigenous communities. But theatre kept pulling at her. Later, as a theatre practitioner, she continued working closely with Indigenous women and kept studying and developed nahualismo as a performance practice based on Indigenous notions of transformation. Although trained in European theories and methods, she needed to explore practices stemming from Mesoamerica. “Instead of continuing to see Mexico from the West, [she wanted to] learn to see the West from Mexico.”

“We are always thinking about how to decolonize ourselves because everything we have learned in school comes from Europe, from the West, and here we have an extraordinary culture that is still alive and continues to give us a different worldview. Why do we use European acting techniques? I don’t mean to say that Meyerhold’s or Stanislavski’s or Grotowski’s research is not good. But why don’t we look for an acting technique based on our culture which is so rich and so different?”

Jesusa’s performances—onstage and off—explore this concept of transformation, as opposed to the phenomenological inquiry of most Western theatre focused on the embodied, first-person experience of appearances of ‘other’ things and situations. “It’s a different worldview and understanding of the human body,” she explains. “When you divide your body in a different way, which isn’t the way you’re used to dividing it, you feel other things. When you name your body in a different way, you feel it in a different way.” This realization allows her to reframe her approach to performance. “Suddenly people started asking me, ‘How can you look so much like President Salinas, or Carlos Monsiváis, or Marilyn Monroe?’ And I’d say no, ‘it’s not that I’m identical, because it’s not enough for you to just wear the mask or the costume of a certain character to look like him. The question is rather: What goes on beyond the costume?’”

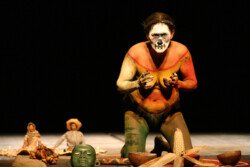

Nahualismo, she explains in Chapter Four, Nahualismo: The Aztec Method of Acting, goes beyond the costume. There she explains what the Nahuas (or Aztecs) considered the different body parts and how that understanding enables her to engage the different ‘entidades anímicas’ or animating energy. As method, this different sense of the body opens different channels for the transformational process. This allows her to tap into the essence of another being, “at will” (reminiscent of what Martínez said of the nahualli). The ‘other’ she becomes speaks and acts through her. Is this a shamanistic practice, an integration, a becoming one, rather than a doubling? Or are the two bodies visible—Jesusa and Malinche? Or is this the theatrical not/not not that Richard Schechner describes? The actor playing Hamlet is not Hamlet, but he’s not not Hamlet. Her Malinche, the 16th century Indigenous woman who served as translator/ companion/ lover to Hernán Cortés, giving birth to the ‘mestizo’ race, reemerges throughout Jesusa’s career since 1980. Back then, she wore the headphones of a well-known local newscaster and presents her own show, “In Direct Silence.” Malinche is hilarious as she performs and re-performs the ever changing and ongoing history of conquest and resilience. As witness and chronicler of an ever-unfolding catastrophe, she is slippery, complicit, opportunistic, and comically devious. Through her sly humor, her play on words, her feigned knowledge and feigned ignorance, Malinche manipulates everything around her to survive. Why does Jesusa continually incarnate her? Malinche touches on the urgent issues of the moment—the never-ending colonization and coloniality of Mexico, political corruption, the faulty infrastructure in Mexico City. While Jesusa seeks to connect to the ancient Mesoamerican cosmologies, she is a thoroughly contemporary creator. How long will Jesusa keep updating Malinche? “Until the country is re-Indianized” through the process of nahualización. When we accept that humans are not the center of the universe, that everything is alive and interconnected, we are becoming nahualizada/os. The verbs to nahualizar (others) and nahualizarse (a reflexive verb meaning to transform ourselves) capture the ability to change shape, positionality, and identity (including gender identity) through metaphysical transformation. Jesusa embraces its potential: “the important thing about performance,” she claims onstage in one of her many roles, “is that it places spectators before their own capacity for transformation–male, female, bird, shoe…” Not recognition. Not identification. Transformation.

This vision of transformation enables us to reconsider Western notions of ‘authenticity.’ Can Jesusa, or anyone, transform themselves into something else? Even if she could, does she have a right to do so? That depends.

From a Mesoamerican perspective, that envisions everything as the entangled, ever-changing manifestation of one essence, the notion of authenticity (etymologically from “Greek authentikos ‘original, genuine, principal,’ from authentes one acting on one’s own authority”) holds no sway. Everything transforms, everything is connected—there is no ‘true’ or ‘false.’

Most of us reading this, however, are not products of Mesoamerican metaphysical thought, so the question means something different. The context clearly determines the nature of the question. From this perspective, we can note that practices such as acting, shamanism, and nagualismo all entail transformation. Yet each depends on its social context for meaning making. Nahuales, for examples, exist as a live presence in the Indigenous social and philosophical worlds that embrace them. “Nahuales don’t exist without a society that validates them,” says Roberto Martínez. For people outside those communities, the relationship might entail the metaphorical or theatrical or speculative ‘as if.’

In other contexts, the oneiric powers associated with nahual and the nahualli might be associated with dreaming and dreamtime. Anzaldúa recognized that “[d]reaming is the nagual’s journey” (34). Hallucinogenic plants create experiences that might resemble the transformational force of the nahual. In Western societies ‘genius’ or ‘schizophrenic’ or ‘possessed’ might refer to individuals with seemingly supernatural or mystifying powers.

Given the centuries old colonialist appropriation of Indigenous ideas, technologies, and practices, however, some might consider the fact that Jesusa would ‘take on’ the mantle of Indigenous philosophy egregious. It might seem as one more act of appropriation. I would argue the opposite. Jesusa takes Mesoamerican philosophy seriously, as original and foundational to Mexico. Following Guillermo Bonfil Batalla’s México Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization, she recognizes that two civilizations constitute and coexist in modern Mexico—the ancient, ‘profound’ Indigenous civilization that has transformed and survived over five hundred years of colonization, and the ‘imaginary’ one, the one that has adopted Western economic, social, and philosophical models. For her, and for peoples rooted in the Indigenous Americas she finds ‘México profundo’ system of thought more compelling and urgent than Western Philosophy. Jesusa never claims to ‘be,’ or ‘become’ Indigenous. At most, through her decades-long work with Indigenous communities, she would like to be recognized as an ‘ally.’ What she strives for, as she puts it, is to ‘nahualizarse,’ to transform herself and her work based on a metaphysical system indigenous to Mexico. Instead of making an identitarian claim, she makes a philosophical one, rejecting the idea that Western philosophy is the universal and only system of thought that deserves the name ‘philosophy.’ The rejection of the ethnocentric privileging of Western philosophy had been advanced by Latin American(ist) scholars such as Miguel León Portilla published his monumental La Filosofía Nahuatl in 1956, Eduardo Vivieros de Castro’s Cannibal Metaphysics in 2009, and James Maffie’s Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion in 2014, and by Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, critical theorists, and artists across the Americas. As we shall see, Jesusa makes a performatic claim by reclaimed the Mesoamerican heritage in her own way, through performance.

Nahualismo expands Western notions of transformation in Western performance. While several 20th century theatre artists, Brecht, Boal, Barba to name a few, worked extensively with the epistemic and political dimensions of transformation, Jesusa also recognizes shape shifting as a way of being in motion, of communicating, surviving, and acting. Like Artaud, who visited the Tarahumara in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, she understands art and culture not as separate from life, but as organic and integral to the expanded understanding of life itself: “Mexicans seek contact with the Manas, forces latent in every form…. springing to life by magic identification…” (Artaud, 11). Instead of the Theatre and Its Double, she writes of the ‘Theatre and Its Nahual.’ Like Tomson Highway, performing and creating laughter are her ways to combat extinction. Like Gloria Anzaldúa, she acts knowing that she is/has a force that’s entangled with everything around her. But Jesusa also ‘dissimulates.’ Her performances are always strategic, aimed at political efficacy. Throughout her career she has insisted that performance must address immediate issues—in whatever style, tone, topic, method the artists choose. As Coatlicue, the mother of the gods, Jesusa inhabits the enormous costume, does a song and dance and complains that Mexicans have forgotten their past, burying their ancestral knowledge in museums. As an activist, she staged battles between good and evil where the ‘People of Corn’ were good and Monsanto was evil. As Senator she staged skits and plays in the Senate (another stage) advocating, among other things, for the legal recognition of Indigenous people’s rights, protection of native corn (indigenous to Mexico) and animal rights—all added to the Mexican Constitution due to her efforts. After decades of trying, Monsanto abandoned attempts to plant its genetically modified corn in Mexico, either experimentally or commercially. Even Mexico’s political opposition was moved and voted in favor. Her powers of persuasion are such that “Jesusa persuades God to become a devil and the devil to dress up as an angel. What she wants, she gets.” Transformation on all levels.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.